Choosing Connection in the Kathmandu Valley

The author, at right, making plates in a workshop. Photo by Saurav KC.

The author, at right, making plates in a workshop. Photo by Saurav KC.

A rising tide lifts all boats in a former lakebed that’s now a capital city surrounded by many smaller, often overlooked communities no less deserving than a Himalayan summit.

NEPAL — I cringed earlier this year when actor Parker Posey, playing a woman of my generation on the hit HBO show White Lotus, said, after being asked by her husband if she thought she’d be okay if they lost all of their money, “I just don’t think, at this age, I’m meant to live an uncomfortable life. I don’t have the will.”

Internet entrepreneurs rushed to print T-shirts with the quote, and it’s echoed in my head hundreds of times over the last few months. It made me think long and hard about the courage needed to close the gap between yourself and others unlike you.

I’ve never contemplated climbing a mountain — much less to the highest point on earth — which is how most travelers find themselves in Nepal. When I got the invitation to visit the country, my curiosity led me to a map: Locked in on three sides by India, with China’s Tibetan region to its north, the largely isolated country wasn’t on my travel bucket list. I had, however, asked the universe to send me an adventure.

Which is how in May, I joined nearly 30 other journalists, influencers, and travel agents from around the world for an immersive trip sponsored by the Nepal Tourism Board and Community Homestay Network (CHN) to discover a side of the country that’s not Mount Everest.

This shared journey of inclusivity, cultural preservation, and economic sustainability aimed to further develop a tourism model established more than a decade ago in one of the world’s least developed countries.

About a third of the group went to towns and villages around the capital city, Kathmandu. Different trips took two other groups to lesser-known corners of the country. We all primarily stayed in the homes of local residents, with scattered nights in small hotels.

The word "homestay" may be self-explanatory, but it elicits raised eyebrows and hesitation bordering on concern. Most Americans are reluctant to overnight with strangers in lieu of hotels or Airbnbs, but homestays have been part of traveling in Nepal since the late 1990s.

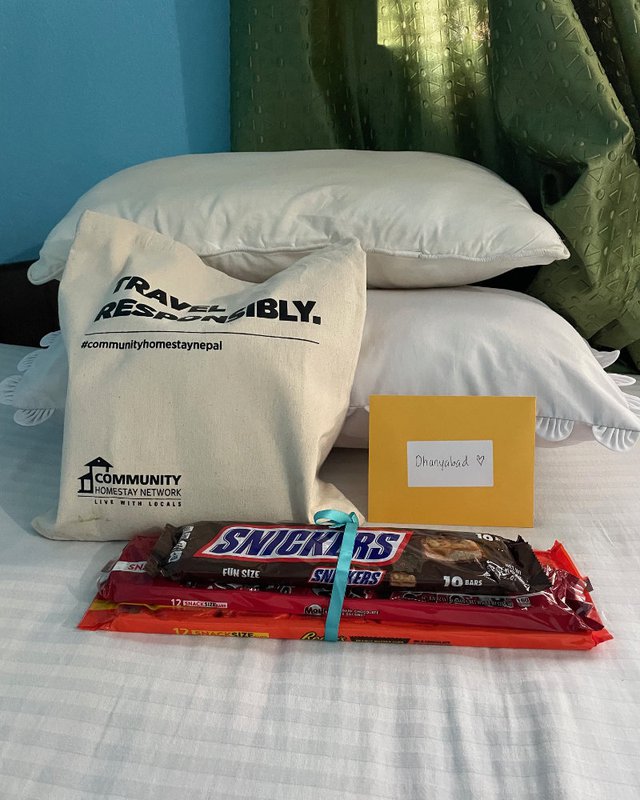

CHN launched in 2017 with a single family in the village of Panauti, about twenty miles outside the capital, with the goal of helping communities with homestays organize, develop, and manage tourism efforts. Today, CHN facilitates homestays in 40 locales and connects tourists with experiences in ten others. Workshops such as wood carving in Bungamati and mask painting in Thimi not only celebrate artisanal efforts, they also help the current generation pass these skills to the next.

Those willing to set aside first-world expectations and meet another culture on its own terms are rewarded with the heartfelt connections CHN fosters. Entire communities benefit from the tourism dollars that flow in, but perhaps no one gains more than the women who run the homestays.

Once Reliant on Husbands, “Now We Have Something"

Trekking up a mountain is a big thing, but little things can also be grand, which is the case with the bedroom communities just outside bustling Kathmandu. They are filled with residents eager to share their lives with travelers open to stepping off the beaten path.

Ganga Devi Hayanju and Dilip Maharjan are two of those people. The couple lives in Kirtipur and hosted three from our small group for two nights in the ancient center of Newar culture. (Our group was divided among three houses.)

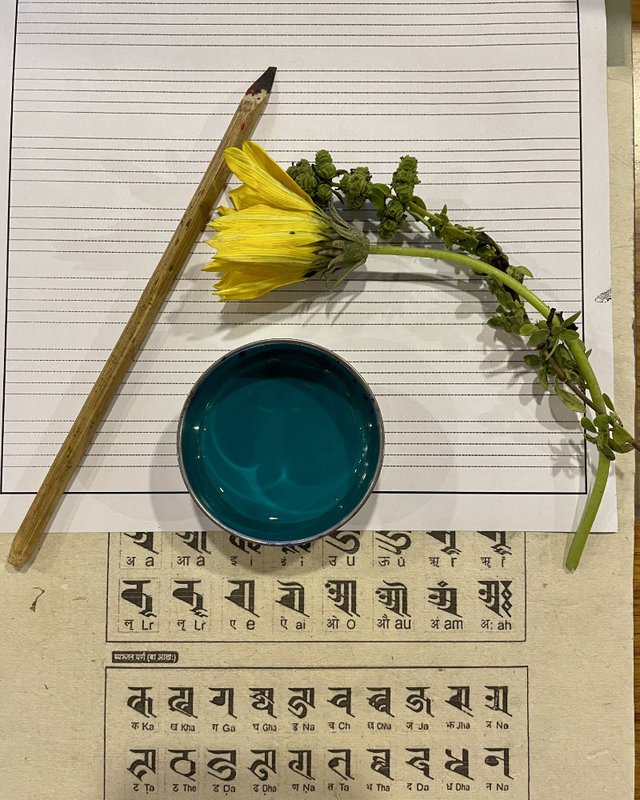

The Newars, a distinct ethnicity descended from those who inhabited the area in prehistoric times, proudly steward age-old cultural and religious traditions. We shared meals with our hosts, wandered through the town square in the early hours when people come to sell and buy vegetables, observed morning prayers in the main temple, and participated in a class to learn to write in a vanishing script used to decorate temple walls and prayer wheels.

When we visited, Ganga and Dilip were expecting their first child. A woman with a smile like sunlight, Ganga patted her round belly in apology for not helping us carry our luggage up flights of stairs to our rooms. She settled us in with tea and a sunset chat on the rooftop before excusing herself to cook dinner while we three guests enjoyed the 360-degree view of the neighborhood and tried to discern Mount Everest through the clouds.

A typical Newari meal consists of steamed rice, lentil soup, a variety of cooked green vegetables, and an assortment of pickles. Our dinner, like our lunch earlier in the day, was just that minus the pickles. Instead, we had fresh cucumber, carrot, radish.

Ganga and Dilip are experienced hosts, with a home rebuilt after the 2015 earthquake that damaged or destroyed 600,000 buildings in Kathmandu and nearby towns and killed about 9,000 residents. Dilip works repairing motors; Ganga has a law degree and a regular teaching job. She speaks enough English for guests to feel comfortable and called the homestay her side gig.

Her situation is unusual for homestay hosts, and it demonstrates the shift in gender roles underway in patriarchal Nepal. Most women still rely on their husbands for financial support and decisions about how to spend the family income. I met many women for whom homestay money is the first money they’ve ever called their own.

Tourism plays a crucial role in Nepal’s economy, and female leadership is a central aspect in this rising tide. Homestays empower women who have traditionally been relegated to cooking, cleaning, and childcare with opportunities they’ve never had before.

Prem Mati Tilijha, part of Narchyang Community Homestay, near Mount Everest’s Annapurna North Base Camp trek, which I did not visit, says, “The money I make through the homestay helps me fulfill my needs. Now, my husband and son ask me for money, which makes me proud. Times back, I was the one asking my husband for money, but now I am the one who gives.”

After her phone was damaged, Kabita Raut Maharjan was able to buy herself a new one. That might not seem like a big deal to you and me, but it was a moment of extreme pride for the Kirtipur Community Homestay host. She giddily recalled how earlier in the day she’d been able to make the purchase on her own.

Women like Prem, Kabita, and Ganga are elevating not only their own lives but also the lives of their neighbors.

Ganga is one of a group of indigenous women who lead Kirtipur Community Homestay, along with a few men. In addition to hosting travelers, the women are also responsible for a very popular momo-making experience. Momos are Nepalese steamed dumplings.

In 2024, 1,126 tourists crafted and consumed roughly 11,000 of these delicious pleated pouches during the workshop. The ladies share not only their recipes but also tales of the growing sense of independence their income is giving them.

Change Isn’t Always Easy

You may wonder why the women of the homestays are getting to keep their earnings when, in almost every case, a man is the legal owner of the house. The homestay model intentionally shifts this dynamic by recognizing women as the primary hosts and income earners.

“When a homestay joins the CHN platform, we work closely with the community to ensure that the woman of the house is the main point of contact, host, and income recipient,” says CHN Chief Executive Officer Aayusha Prasain. “We actively encourage women to open their own bank accounts and help build formal financial channels that provide them with greater autonomy and control over their income.”

This shift isn’t happening without resistance. In some communities, women are opening bank accounts for the first time, and the idea of women managing finances can be met with hesitation, sometimes even opposition. “Through multiple rounds of community consultations and family meetings, we engage with both men and women to help them understand the long-term value of women’s financial inclusion and leadership,” Aayusha says.

Importantly, children and youth within the family and community often play a pivotal role in supporting and advocating for their mothers’ entrepreneurship journeys. Their encouragement helps challenge traditional gender roles and normalize women’s participation in economic activities.

“The shift has been seen with the women and families we are working with. While not every household starts with full gender equity, this model helps create a pathway for women to take greater ownership, both economically and socially,” she says.

A Second Generation Moves the Homestay Movement Forward

CHN Chief Operating Officer Poonam Gupta Shrestha is the daughter of one of the first women to host travelers in Panauti. As a young girl, Poonam helped her mother make guests comfortable in their home. She and her brother spoke English, and they mostly interacted with guests while their mother cooked and cleaned.

“As the women of our community took the lead, including my mother, I found myself playing a unique role — translating for travelers who stayed in our home and helping the women of the homestay learn English. It was here that I witnessed firsthand the transformative power of tourism, not just for travelers but for the families like mine who embraced it,” she says. With homestay money, her family made improvements to their home, including modern amenities like a Western toilet.

Her story is just one example of how upgrades benefit both CHN hosts and travelers. After the 2015 earthquake leveled the homestay village of Nagarkot, which had been operating for only a few years, families rebuilt with guests in mind.

One of six brothers who founded the village in 2011, Puskar Bastola and his wife, Rama, took the opportunity to standardize accommodations at their house, building four guest bedrooms with en suite bathrooms. Such luxuries are not guaranteed to homestay travelers, especially those in more far-flung locales. I stayed with the couple and their son, who has returned home from university to learn to run the homestay village.

Nagarkot lies about 15 miles from Kathmandu, but the journey can take an hour. Roads are bumpy and winding, but the views are worth a Dramamine. The hilly Brahmin community is exceedingly peaceful. Fields of potatoes and cucumbers sprawl through the countryside, and I awoke to the sweetest birdsong each morning at 4:30 sharp.

A manicured forest of tall pine trees, strung with Tibetan prayer flags, stretches for miles behind the Nagarkot Community Homestay, but nothing gives it away. Walking around a corner and into a storybook setting, complete with frothy waterfalls and a suspension bridge spanning hundreds of yards high above the treetops, was a reminder that there’s a whole world waiting to be discovered if we push past the periphery.

Look Inside for the Rewards

But pushing past might prove difficult to sensibilities that aren't up for it. One woman on the trip had a full-blown panic attack over cleanliness, or what she felt was the lack thereof, and had to be extracted. On a trip to a much more rural part of the country, two people requested to stay in other accommodations than the homestay.

This had me doing a whole psychological study on myself as a traveler. I realized I would sleep in a ditch with eels before I’d dare embarrass someone who was showing me hospitality and kindness. Over eight days in the Kathmandu Valley, I slept in humble beds, drip dried without a towel, and let go of my cravings for hot lattes. I was even leeched on a walk through the hills. The discomforts dissolved in the richness of the experience.

What is hard to find in a world of phony, overly polished moments masquerading as authenticity is abundant in Nepal. In the quiet rhythms of daily life, in the people and places that don’t make headlines, the country offers culture and traditions that are lived, not performed. You must, however, have the will to choose connection over convenience and sustainability over souvenirs.

That last part was admittedly tough. The American in me wanted to shop.

Plan Your Trip

Ready to take your own cultural journey through the Kathmandu Valley? To engage with artisans in Bungamati, cook momos in Kirtipur, hike to Nagarkot, and connect with local people via homestays? Book through Community Homestay Network. The $1,985 per person (USD) fee for a week-long trip includes a local English-speaking guide, ground transportation, accommodations, listed hands-on experiences, plus most meals. It does not include flights and the Nepal visa fee ($30 when I traveled).